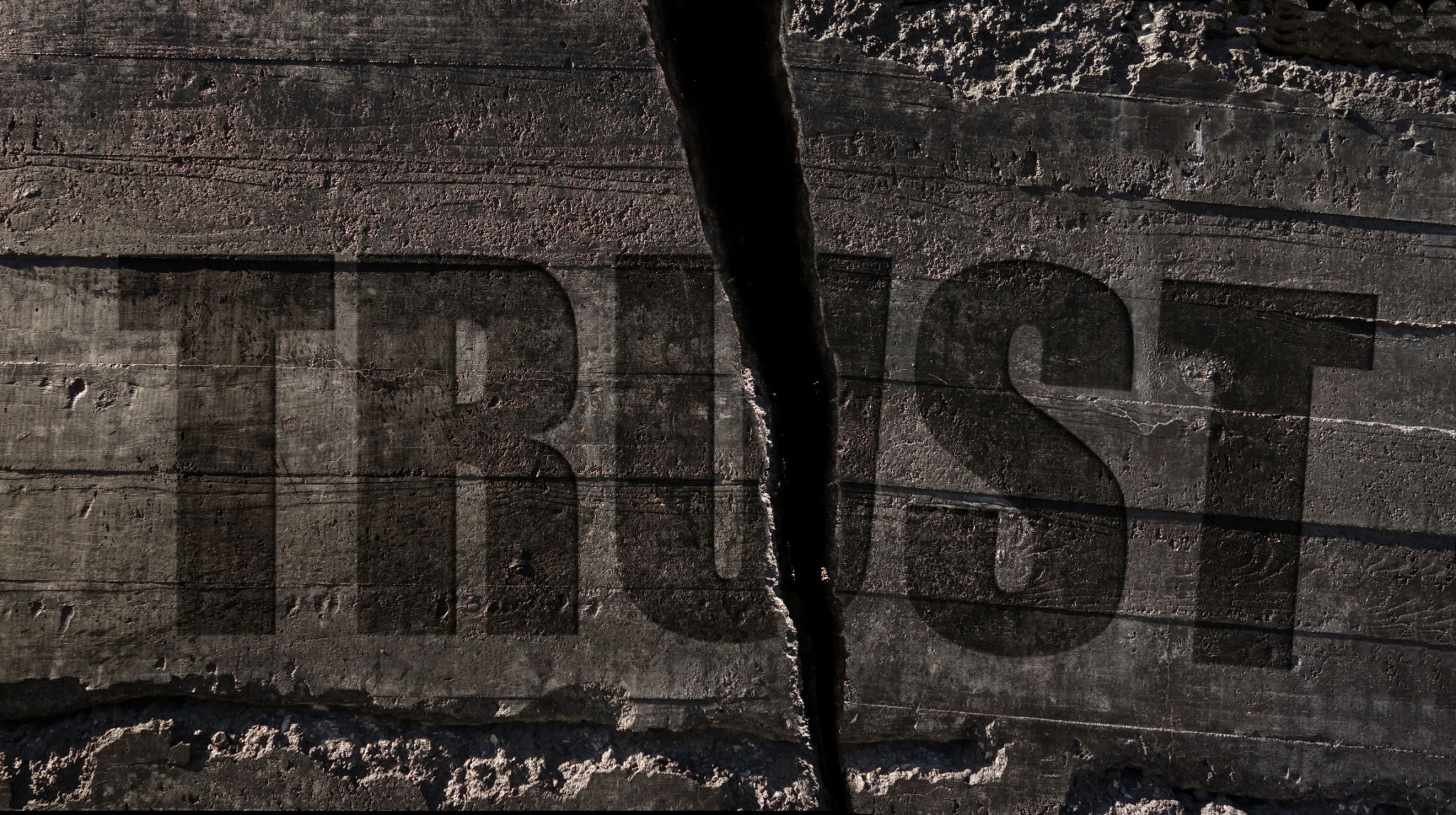

“Trust No One” May Be The Worst Advice You Could Ever Take; Here Is Why

If you find this article relevant and that it resonates for you, you may also enjoy reading my book about this and similar topics, "Life Is Swweter Within", and enjoy 20% off the ebook versions, if you order within the next two weeks, by entering the discount code "SAVE20" at checkout.

Introduction: The Invisible Foundation of Human Life

Imagine waking up tomorrow in a world where trust had vanished overnight. You wouldn't drink the water from your tap, uncertain if it was safe. You wouldn't drive to work, unable to trust that other drivers would follow traffic laws. You wouldn't buy groceries, uncertain if the food was what it claimed to be. You wouldn't check your bank balance, unable to trust that your money was secure. Within hours, modern civilization would collapse not from any external threat, but from the absence of something so fundamental we rarely notice its presence: trust.

Trust operates as the invisible infrastructure of human existence, much like the electrical grid that powers our cities. We only notice it when it fails, yet it underlies nearly every interaction, transaction, and relationship in our lives. From the psychological perspective, trust serves as a cognitive shortcut that allows us to navigate an impossibly complex social world without being paralyzed by uncertainty. From the sociological lens, trust functions as the binding agent that holds communities, institutions, and entire societies together.

Understanding trust becomes even more crucial when we recognize that people approach it in fundamentally different ways. Some individuals operate from what researchers call a "trust verification" model, where trust must be earned through demonstrated reliability and good intentions over time. Others embrace a "trust assumption" model, extending trust readily to new people and situations, only withdrawing it when betrayed. Both approaches represent valid psychological adaptations to the human condition, yet both require us to maintain our fundamental capacity to trust if we hope to thrive individually and collectively.

This exploration will take you through the psychological foundations of trust, examine how it impacts both personal wellbeing and societal functioning, help you understand your own trust orientation, and ultimately demonstrate why continuing to trust others remains one of the most important choices we can make for ourselves and our world.

The Psychological Architecture of Trust

To understand why trust matters so profoundly, we must first examine how it develops in the human mind and what purposes it serves. Trust represents one of humanity's most sophisticated psychological tools, emerging from the intersection of cognition, emotion, and social learning.

The foundation of our trust capabilities begins in infancy through what developmental psychologist Erik Erikson identified as the first psychosocial crisis: basic trust versus mistrust. During the first year of life, infants learn whether their caregivers will reliably meet their needs for food, comfort, and affection. When caregivers respond consistently and sensitively, infants develop what Erikson called "basic trust" – a fundamental sense that the world is predictable and that others can be relied upon. This early experience creates what researchers now call "trust schemas" – cognitive frameworks that shape how we interpret and respond to trustworthiness cues throughout our lives.

Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, provides deeper insight into how these early experiences influence our adult trust patterns. Children who experience secure attachment – characterized by responsive, consistent caregiving – typically develop secure internal working models of relationships. These mental templates lead them to expect that others will be available and supportive when needed, creating what psychologists term "high trust propensity." In contrast, children who experience inconsistent or unresponsive caregiving may develop anxious or avoidant attachment styles, leading to more cautious approaches to trust in adulthood.

The neuroscience of trust reveals fascinating insights about its biological underpinnings. When we decide to trust someone, multiple brain systems activate simultaneously. The prefrontal cortex engages in complex risk-benefit calculations, weighing potential gains against possible losses. The limbic system, particularly the amygdala, scans for threat signals that might indicate untrustworthiness. Meanwhile, the release of oxytocin, often called the "trust hormone," facilitates bonding and reduces fear responses that might inhibit trusting behavior.

Research by neuroeconomist Paul Zak has shown that trust literally changes our brain chemistry. When someone places trust in us, our brains release oxytocin, which not only makes us feel good but also increases our likelihood of acting in trustworthy ways. This creates what Zak calls the "trust-trustworthiness cycle" – a positive feedback loop where trust begets trustworthiness, which in turn generates more trust.

From a cognitive perspective, trust serves as what psychologists call a "social heuristic" – a mental shortcut that allows us to make quick decisions about whom to rely on without conducting exhaustive investigations. Without trust, every social interaction would require extensive verification and monitoring, making normal social life impossible. Trust allows us to delegate, collaborate, and build upon others' work, creating the foundation for complex human achievements.

Trust and Individual Health: The Personal Benefits of Trusting

The impact of trust on individual health and wellbeing extends far beyond its social benefits, reaching into the very core of our physical and mental health. Research consistently demonstrates that people with higher levels of trust experience better health outcomes across multiple domains, while those with chronic mistrust face significant health penalties.

The physiological effects of trust begin with stress reduction. When we trust others, we activate what researchers call the "tend and befriend" response rather than the more familiar "fight or flight" reaction. This trust-based response is associated with lower levels of cortisol, the primary stress hormone that, when chronically elevated, contributes to cardiovascular disease, immune suppression, and cognitive decline. Studies by health psychologist Sheldon Cohen have shown that people who report higher levels of social trust have stronger immune responses to vaccines and are less susceptible to common cold viruses when exposed.

The cardiovascular benefits of trust are particularly striking. Research published in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that people with high levels of social trust had significantly lower rates of coronary heart disease, even after controlling for traditional risk factors like smoking, exercise, and diet. The mechanism appears to involve both direct stress reduction and indirect behavioral pathways – trusting people are more likely to seek medical care when needed, adhere to treatment recommendations, and maintain social connections that buffer against health risks.

Mental health outcomes show even more dramatic associations with trust levels. People with higher trust propensity report lower rates of depression and anxiety, greater life satisfaction, and higher levels of subjective wellbeing. This relationship appears to work through multiple pathways. Trust facilitates the formation and maintenance of social relationships, which provide emotional support, practical assistance, and meaning in life. Additionally, trusting people are more likely to interpret ambiguous social situations positively, reducing the cognitive burden of constantly scanning for threats.

The concept of "social capital," developed by sociologist James Coleman and popularized by political scientist Robert Putnam, helps explain why trust translates into better individual outcomes. Social capital represents the resources available to individuals through their social networks – everything from job opportunities and business partnerships to emotional support and practical help. Trust serves as the currency of social capital, determining how much individuals can access and benefit from their social connections.

Research on longevity provides perhaps the most compelling evidence for trust's health benefits. The Harvard Study of Adult Development, which has followed participants for over 80 years, consistently finds that the quality of relationships is the strongest predictor of long-term happiness and health. Within this research, trust emerges as a key component of relationship quality, with trusting individuals living longer, healthier lives than their more suspicious counterparts.

The psychological mechanisms underlying these health benefits involve what researchers call "broaden and build" effects. When we trust others, we experience positive emotions that broaden our awareness and build our psychological resources. We become more creative, more optimistic, and more resilient in facing challenges. This upward spiral of positive emotions and expanded capabilities contributes to what psychologists call "flourishing" – a state of optimal psychological functioning.

However, it's important to recognize that the health benefits of trust depend on what researchers call "calibrated trust" – trust that is appropriately matched to the trustworthiness of others and situations. Blind trust that ignores obvious warning signs can lead to exploitation and trauma, while excessive mistrust isolates us from beneficial relationships. The key lies in developing what some researchers call "smart trust" – the ability to extend trust wisely while remaining open to positive relationships.

Trust as the Foundation of Society: Collective Wellbeing and Social Functioning

While trust's benefits for individuals are substantial, its role in societal functioning is even more fundamental. Trust operates as what sociologists call the "social glue" that binds communities together and enables complex forms of cooperation that define human civilization. Without trust, societies cannot develop the sophisticated institutions, economic systems, and cultural achievements that characterize advanced human communities.

Economic systems provide the most obvious example of trust's societal importance. Every economic transaction, from purchasing groceries to international trade agreements, relies on trust. When you buy something with a credit card, you trust that the merchant will provide the goods or services promised, while the merchant trusts that your bank will transfer the payment. This simple transaction involves trust in multiple institutions: banks, credit card companies, legal systems, and regulatory agencies. Economic research by Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow has shown that societies with higher levels of generalized trust have more efficient markets, lower transaction costs, and higher rates of economic growth.

The concept of "institutional trust" helps explain how trust scales up from individual relationships to societal functioning. Political scientists distinguish between interpersonal trust (trust in specific individuals) and institutional trust (trust in organizations, systems, and abstract entities). While interpersonal trust forms the foundation, institutional trust allows societies to coordinate the behavior of millions of people who will never meet each other.

Consider the simple act of driving a car. Every time you enter traffic, you place your life in the hands of countless strangers, trusting that they will follow traffic laws, maintain their vehicles properly, and drive responsibly. This trust isn't based on personal knowledge of individual drivers but on confidence in the system of driver education, vehicle inspection, traffic enforcement, and legal consequences that shape driving behavior. When this institutional trust breaks down, as it has in some societies experiencing political upheaval, traffic accidents increase dramatically.

Democratic governance represents perhaps the most complex form of trust-based social organization. Democracy requires citizens to trust that elections will be conducted fairly, that elected officials will act in the public interest (at least to some degree), and that peaceful transfers of power will occur when new leaders are chosen. Research by political scientist Robert Putnam has shown that regions with higher levels of social trust are more likely to develop effective democratic institutions and maintain political stability over time.

The relationship between trust and social capital extends beyond individual benefits to create what economists call "positive externalities" – benefits that extend beyond the immediate participants in trusting relationships. When people in a community trust each other, they are more likely to cooperate on public goods like schools, parks, and infrastructure. They are more willing to volunteer for community organizations, participate in civic activities, and help neighbors in times of need. This creates a virtuous cycle where trust generates community benefits that, in turn, create conditions that foster more trust.

Research on "social cohesion" demonstrates how trust contributes to societal resilience in facing challenges. Communities with higher levels of social trust recover more quickly from natural disasters, experience lower crime rates, and show greater economic mobility across generations. The September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States provide a striking example of how trust can emerge from crisis – communities with strong social bonds before the attacks showed remarkable cooperation and mutual aid in the aftermath, while more fragmented communities struggled to coordinate effective responses.

The concept of "generalized trust" – the belief that most people can be trusted most of the time – serves as a particularly important predictor of societal wellbeing. Societies with high levels of generalized trust, such as those found in Scandinavian countries, consistently rank highest on measures of happiness, life satisfaction, and social welfare. These societies have developed what researchers call "high-trust equilibrium" – a stable pattern where most people act trustworthily because they expect others to do the same, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of cooperation and social benefit.

Understanding Your Trust Orientation: Two Paths to Social Connection

As we've established, trust serves crucial functions for both individuals and society, but people approach trust in fundamentally different ways. Understanding your own trust orientation can help you leverage your natural tendencies while avoiding potential pitfalls. The two primary orientations – trust verification and trust assumption – represent different but equally valid strategies for navigating social relationships.

The trust verification approach, sometimes called "earned trust" or "slow trust," reflects what psychologists term low trust propensity. People with this orientation begin new relationships with healthy skepticism, gradually building confidence in others through repeated positive interactions. They operate from the principle that trust is a valuable resource that should be invested carefully, based on evidence of reliability, competence, and good intentions.

This approach often develops from experiences that taught the importance of caution in relationships. Perhaps you grew up in an environment where promises were frequently broken, or you experienced betrayal in important relationships. Maybe you work in a profession where verifying information and credentials is essential for safety or success. These experiences create what psychologists call "trust trauma" – not necessarily dramatic events, but patterns of experience that teach us that trust must be earned rather than freely given.

People with trust verification orientations tend to be excellent at what researchers call "trust calibration" – matching their level of trust to the actual trustworthiness of others. They are less likely to be victims of fraud or exploitation because they naturally investigate and verify before committing. They often excel in roles that require careful evaluation of others, such as management, law enforcement, or financial services.

However, the trust verification approach can also create challenges. Because building trust takes time, these individuals may miss opportunities for beneficial relationships or collaborations. They may be perceived as cold or distant by others who extend trust more readily. Most importantly, they may become trapped in what researchers call the "trust paradox" – the more they protect themselves from betrayal, the less they experience the benefits that come from trusting relationships.

The trust assumption approach, also known as "swift trust" or "presumptive trust," reflects high trust propensity. People with this orientation extend trust readily to new people and situations, operating from the belief that most people are fundamentally good and trustworthy until proven otherwise. They start relationships with openness and vulnerability, creating conditions that often encourage others to respond with trustworthiness.

This approach typically develops from secure early relationships that taught that others are generally reliable and well-intentioned. People with trust assumption orientations often grew up in stable, supportive environments where promises were kept and help was available when needed. They learned that opening themselves to others generally leads to positive outcomes, creating what psychologists call "trust resilience" – the ability to continue trusting even after experiencing occasional betrayals.

The benefits of the trust assumption approach are substantial. These individuals form relationships more quickly and deeply, creating rich social networks that provide emotional support, practical assistance, and opportunities for growth. They are more likely to be trusted by others because their openness invites reciprocity. They often excel in roles that require building rapport quickly, such as sales, counseling, or team leadership.

Yet the trust assumption approach also carries risks. People who trust too readily may become victims of manipulation or exploitation. They may ignore warning signs of untrustworthiness because their default assumption is that others mean well. They may experience more frequent betrayals because they expose themselves to more potential betrayers.

To determine your own trust orientation, consider how you typically respond to new people and situations. When you meet someone new, do you assume they are trustworthy until they prove otherwise, or do you assume they must prove their trustworthiness before you trust them? When someone asks for your help or support, is your first instinct to provide it, or to understand their motivations first? When you hear gossip or criticism about someone you know, do you tend to give that person the benefit of the doubt, or do you wonder if the criticism might be accurate?

Consider also your emotional responses to trust decisions. Do you feel energized by the vulnerability of trusting someone new, or do you feel anxious about potential betrayal? When someone disappoints you, do you tend to assume it was an honest mistake or wonder if it reveals something about their character? Do you find it easier to forgive and continue trusting, or do you become more cautious in that relationship?

Your trust orientation may also vary across different domains of life. You might be a high-trust person in personal relationships but low-trust in business dealings, or vice versa. You might trust easily in some cultures or communities but not others. Understanding these variations can help you recognize when your natural approach serves you well and when you might need to adjust your strategy.

Why "Trust No One" May Be the Worst Advice You Could Take

Before exploring how both trust orientations can maintain healthy approaches to trusting others, we must confront one of the most destructive pieces of advice commonly offered in our cynical age: "trust no one." This seemingly protective philosophy, often presented as worldly wisdom, may actually represent one of the most harmful approaches to human relationships and social living that one could adopt.

The "trust no one" mentality typically emerges from experiences of betrayal, disappointment, or trauma. After being hurt by someone they trusted, individuals may conclude that the solution is to never trust again. This response is understandable from a pain-avoidance perspective, but research from multiple disciplines reveals it to be profoundly counterproductive for both individual wellbeing and social functioning.

From a psychological standpoint, adopting a "trust no one" approach creates what researchers call "learned helplessness" in social situations. When we refuse to trust anyone, we effectively trap ourselves in a prison of isolation, unable to access the resources, support, and opportunities that come through relationships with others. Studies by social psychologist Shelley Taylor have shown that people who adopt extreme mistrust as a life strategy experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and physical illness compared to those who maintain calibrated trust approaches.

The neurological consequences of chronic mistrust are particularly striking. When we constantly scan for threats and betrayal, our brains remain in a state of hypervigilance that researchers call "chronic stress arousal." This state floods our systems with stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which over time contribute to cardiovascular disease, immune suppression, cognitive decline, and accelerated aging. Essentially, the "trust no one" approach creates a physiological state similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, even in the absence of ongoing threats.

Perhaps more fundamentally, the "trust no one" philosophy contradicts everything we know about human nature and development. Humans evolved as intensely social creatures whose survival depended on cooperation, mutual aid, and group cohesion. Our brains are literally wired for connection, with specialized neural circuits for reading social cues, feeling empathy, and engaging in reciprocal relationships. When we shut down these systems through radical mistrust, we work against our own biological and psychological design.

The social consequences of widespread "trust no one" attitudes are equally devastating. When significant numbers of people in a community adopt this approach, it creates what sociologists call a "low-trust equilibrium" – a stable but destructive pattern where mistrust begets more mistrust. In such environments, cooperation becomes nearly impossible, economic development stagnates, and social problems multiply because people cannot work together effectively to solve them.

Historical examples demonstrate the catastrophic effects of societies where "trust no one" becomes the dominant philosophy. The Cultural Revolution in China, Stalin's purges in the Soviet Union, and the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia all created environments where trusting anyone – even family members – could be fatal. The result was not greater safety but rather social collapse, economic devastation, and immense human suffering. These extreme examples illustrate the logical endpoint of "trust no one" thinking when applied at scale.

Even in less dramatic contexts, research shows that communities with low trust levels experience higher crime rates, reduced economic mobility, poor educational outcomes, and decreased civic participation. When people cannot trust their neighbors, local institutions, or community leaders, they become unable to coordinate collective action for mutual benefit. The result is a downward spiral where mistrust creates conditions that justify more mistrust.

The "trust no one" approach also fails on its own terms as a protective strategy. Paradoxically, people who trust no one often become more vulnerable to exploitation, not less. Because they cannot build genuine relationships, they lack the social networks that provide information about threats and opportunities. Because they cannot evaluate trustworthiness cues accurately (having decided in advance that no one is trustworthy), they may miss obvious warning signs about genuinely dangerous individuals while rejecting potentially beneficial relationships.

Moreover, the "trust no one" mentality often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. When we approach others with suspicion and hostility, we often provoke exactly the untrustworthy behavior we expect. People respond to mistrust with withdrawal, defensiveness, or reciprocal mistrust, confirming our negative expectations and reinforcing the cycle.

Perhaps most tragically, "trust no one" represents a surrender of one of humanity's greatest capacities – the ability to form deep, meaningful connections with others that transcend immediate self-interest. When we refuse to trust anyone, we forfeit access to love, friendship, mentorship, collaboration, and all the other forms of human connection that give life meaning and purpose. We may protect ourselves from betrayal, but only by ensuring that we never experience the full richness of human existence.

The alternative to "trust no one" is not "trust everyone" – another extreme that ignores legitimate risks and dangers. Instead, the evidence supports what we might call "smart trust" or "calibrated trust" – approaches that maintain openness to trusting while developing the skills to assess trustworthiness accurately and adjust trust levels appropriately based on evidence and context.

This means learning to distinguish between being prudent and being paranoid. Prudence involves taking reasonable precautions, verifying important claims, and maintaining appropriate boundaries. Paranoia involves assuming everyone has malicious intent, interpreting ambiguous behavior as threatening, and rejecting opportunities for connection based on imagined rather than real risks.

The key insight is that trust involves risk, but so does mistrust. The question is not whether to take risks, but which risks are worth taking based on the potential costs and benefits. Research consistently shows that the risks of appropriate trust are generally far outweighed by the benefits, while the risks of radical mistrust – isolation, missed opportunities, poor health, and social dysfunction – are severe and often irreversible.

The Imperative to Continue Trusting: Why Both Orientations Must Maintain Faith in Others

Regardless of whether you naturally lean toward trust verification or trust assumption, the most crucial insight from psychological and sociological research is clear: we must continue trusting others if we hope to thrive individually and collectively. This doesn't mean trusting blindly or ignoring red flags, but rather maintaining what researchers call "openness to trust" – the fundamental willingness to extend trust when circumstances warrant it.

For those with trust verification orientations, the challenge lies in not allowing past disappointments or natural caution to close off opportunities for meaningful connection. Research shows that overly cautious people may develop what psychologists call "trust avoidance" – a pattern of behavior that prevents them from accessing the benefits of trusting relationships. The key is learning to calibrate trust appropriately, extending it when evidence suggests it's warranted while maintaining appropriate boundaries.

This calibration involves what researchers call "graduated trust" – starting with small trust investments and gradually increasing them as the other person demonstrates reliability. Rather than seeing trust as an all-or-nothing proposition, treat it as a process of mutual discovery. Share something small and observe how it's handled. Ask for a minor favor and see if it's fulfilled. Look for consistency between words and actions over time.

For those with trust assumption orientations, the challenge involves maintaining openness while developing better "trust radar" – the ability to recognize situations and individuals that may not deserve immediate trust. This doesn't require becoming suspicious or cynical, but rather developing what researchers call "mindful trust" – conscious awareness of trust decisions rather than automatic trust extension.

Mindful trust involves paying attention to your own internal responses to people and situations. Notice when something feels "off" even if you can't articulate why. Trust your intuition while also gathering more information. Ask questions about inconsistencies rather than ignoring them. Remember that trusting someone doesn't require trusting them with everything immediately.

The reason both orientations must maintain their capacity to trust lies in what researchers call the "trust imperative" – the fact that human beings are fundamentally interdependent creatures who cannot thrive in isolation. Our biology, psychology, and social nature all evolved in the context of cooperative groups where trust was essential for survival and flourishing.

From a biological perspective, humans are born more helpless and dependent than any other species, requiring years of care and support to reach maturity. This extended childhood creates deep psychological needs for connection and security that persist throughout life. Research in social neuroscience shows that social rejection activates the same pain pathways in the brain as physical injury, suggesting that social connection is not a luxury but a basic need.

From a psychological perspective, relationships provide what researchers call "social regulation" – the ability of others to help us manage our emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. When we trust others enough to be vulnerable with them, they can provide perspective on our problems, comfort in times of distress, and celebration of our successes. This social regulation contributes to better mental health, more effective coping with stress, and greater life satisfaction.

From a sociological perspective, individual wellbeing is inextricably linked to the health of our communities and societies. When trust breaks down at the societal level, everyone suffers through increased crime, reduced economic opportunity, political instability, and social fragmentation. By continuing to trust appropriately, we contribute to the social capital that benefits everyone.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides a contemporary example of how trust operates at both individual and societal levels. Regions with higher levels of social trust showed better compliance with public health measures, more effective community support for vulnerable populations, and faster economic recovery. Individuals who maintained trusting relationships during lockdowns showed better mental health outcomes than those who became isolated or suspicious.

Practical Applications: Building and Maintaining Trust in Daily Life

Understanding the importance of trust is one thing; applying this knowledge in daily life is another. Both trust verification and trust assumption orientations can benefit from specific strategies for building and maintaining healthy trusting relationships while protecting against betrayal and exploitation.

For individuals with trust verification orientations, the goal is expanding your capacity to trust without abandoning appropriate caution. Start by identifying areas where your natural skepticism may be preventing beneficial relationships or opportunities. Are there people in your life who have consistently demonstrated reliability but whom you still hold at arm's length? Are there activities or commitments you avoid because they require trusting others?

Practice "trust experiments" – small, low-risk situations where you can practice extending trust. Share a minor concern with a colleague who has shown themselves to be discreet. Ask a neighbor for a small favor. Join a group activity that requires some level of interdependence. Pay attention to how these experiences feel and what you learn about both yourself and others.

Develop what researchers call "trust literacy" – the ability to read trustworthiness cues accurately. Look for consistency between words and actions over time. Notice whether people follow through on commitments, even small ones. Observe how they treat others, particularly those with less power or status. Pay attention to whether they take responsibility for mistakes or blame others. These patterns provide much better indicators of trustworthiness than surface charm or impressive credentials.

For individuals with trust assumption orientations, the goal is maintaining openness while developing better discernment. Start by paying more attention to your own emotional responses to people and situations. When something doesn't feel right, resist the urge to ignore or rationalize away these feelings. Instead, treat them as valuable information that deserves investigation.

Develop what researchers call "trust boundaries" – clear guidelines about what level of trust is appropriate in different types of relationships and situations. You don't need to trust your accountant with your deepest emotional secrets, just as you don't need to trust a casual acquaintance with your financial information. Different relationships warrant different levels of trust, and appropriate boundaries protect both parties.

Practice "trust verification" skills even within your natural trust assumption orientation. When someone makes a significant request or claim, ask for clarification or evidence. When entering into important agreements, put expectations in writing. When someone's behavior seems inconsistent with their stated values, address the discrepancy directly rather than assuming you misunderstood.

Both orientations can benefit from understanding what researchers call "trust repair" – the process of rebuilding trust after it has been damaged. Trust violations are inevitable in any long-term relationship, but they don't necessarily mean the relationship must end. The key factors in trust repair include acknowledgment of the violation, genuine remorse, explanation (not excuse) of what happened, and demonstration of changed behavior over time.

Building institutional trust – trust in systems and organizations rather than individuals – requires different strategies. Research what institutions you rely on and understand how they operate. Participate in civic activities that give you direct experience with how institutions function. Support transparency and accountability measures that make institutions more trustworthy. Remember that institutional trust is built collectively through individual actions and choices.

Conclusion: Trust as a Choice and a Practice

As we reach the end of this exploration, it's important to recognize that trust is ultimately both a choice and a practice. While our early experiences and natural temperament influence our trust orientations, we retain the ability to consciously decide how to approach trust in our daily lives. This choice carries profound implications not only for our personal wellbeing but for the health of our communities and society as a whole.

The research is clear: trust matters enormously for both individual and collective flourishing. People who maintain their capacity to trust experience better physical health, stronger mental wellbeing, more satisfying relationships, and greater life satisfaction. Societies with higher levels of trust enjoy more robust economies, more effective governance, lower crime rates, and greater social cohesion.

Yet trust is not simply something we have or don't have – it's something we do. Every day, we make countless decisions about whether to extend trust, how much trust to offer, and when to adjust our trust levels based on new information. These decisions shape not only our own experiences but also the experiences of those around us and the broader social environment we all share.

Whether you naturally lean toward trust verification or trust assumption, the key is maintaining what we might call "intelligent trust" – the wisdom to extend trust appropriately while protecting yourself and others from harm. This means neither blind trust that ignores obvious warning signs nor cynical mistrust that closes you off from beneficial relationships. Instead, it means developing the skills to read trustworthiness cues accurately, calibrate your trust levels appropriately, and recover from trust violations without abandoning your capacity to trust.

The stakes of this choice extend far beyond our personal lives. In an era of increasing polarization, fake news, and social fragmentation, our individual decisions about trust contribute to larger patterns of social trust or mistrust. When we choose to extend appropriate trust, we contribute to the social capital that benefits everyone. When we model trustworthy behavior ourselves, we encourage others to do the same, creating positive cycles of cooperation and mutual benefit.

Perhaps most importantly, maintaining our capacity to trust is an act of hope – hope that people are generally good, that cooperation is possible, that the future can be better than the past. This hope is not naïve optimism but rather what we might call "practical idealism" – the recognition that our assumptions about others become self-fulfilling prophecies. When we expect trustworthiness and respond to it when we see it, we create conditions that encourage more trustworthy behavior.

Trust, then, is not just a psychological phenomenon or social mechanism – it's a fundamental expression of our humanity. In choosing to trust appropriately, we affirm our interdependence, acknowledge our vulnerability, and commit to the ongoing project of building a world where cooperation and mutual flourishing are possible. This choice, made again and again in countless small interactions, may be one of the most important contributions we can make to our own wellbeing and to the wellbeing of the world we share.